Failed Icons

-

Image courtesy Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP via Getty Images.

Image courtesy Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP via Getty Images.When David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill unveiled the final design of the Freedom Tower last June, Daniel Libeskind, the putative planner of the World Trade Center site, was quoted by the New York Times as saying, "With further refinement it can become an icon for the city." The 102-story skyscraper will certainly be hard to miss, but will that be enough to make it an icon? And what is an iconic building, anyway?

-

CREDIT: Image courtesy Sydney Opera House.

CREDIT: Image courtesy Sydney Opera House.One of the first modern icons was the Sydney Opera House, designed by Jørn Utzon in 1957-73. Upon completion, it was internationally recognized as an Australian symbol. But a symbol of what? According to Charles Jencks, the author of Iconic Building, the white forms can be read as sails, waves, seashells, or copulating turtles. None of which has anything to do with music, but in some vague way seems just right for Sydney's harbor. Jencks defines iconic buildings as delicate balancing acts between what he calls explicit signs and implicit symbols, that is, between an unusual, memorable form and the images it conjures up. He emphasizes that in an increasingly heterogeneous world, multiple and sometimes even enigmatic meanings are precisely what turn a building into a popular icon.

-

Photograph by Carol Pratt. Image courtesy Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C.

Photograph by Carol Pratt. Image courtesy Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C.What Jencks does not say, in his altogether too polite book, is that this balancing act is extremely rare—for every successful icon there are scores of failures. In 1963, Congress mandated that the future national center for the performing arts in Washington, D.C., should honor the slain John F. Kennedy. It was a compelling idea: to commemorate the youthful president not with a shrine or a monument but with a "living memorial." Unfortunately, Edward Durrell Stone's design (which was already under way at the time of the mandate) undermined this worthy intention. Stone modeled the overall form—a box surrounded by columns—on the nearby Lincoln Memorial, and to accentuate the parallel, clad it entirely in white marble. Thus, instead of multiple, enigmatic meanings, there was only one: a temple. A very big temple.

-

CREDIT: Photograph by PictureArts.

CREDIT: Photograph by PictureArts.A successful icon doesn't have to be functional. The Sydney Opera House, for example, didn't make structural sense, cost 10 times its original estimate, and the main hall never really worked well as an opera house (it's now used as a concert hall). Nevertheless, functional failings can sometimes sink a would-be icon. The Olympic stadium in Montreal, designed by the Parisian architect Roger Tallibert for the 1976 Games, was one-of-a-kind, with a retractable fabric roof suspended from steel cables. Since the cables were strung from a tilted, 40-story mast, the iconic ambition of the Leaning Tower of Montreal was plain. However, the roof never worked properly, and, after self-destructing in a high wind, it was replaced by a fixed cover. Although the stadium was used by the Expos, it was always an unpleasant ballpark—too dark, too much concrete, and at a billion dollars, too expensive. Montrealers, who never warmed to the stadium, called it "The Big Owe."

Correction, Aug. 11: The article originally implied that the Sydney Opera House is no longer used for opera. While the main hall is now used as a concert hall, opera is performed in a smaller stage theater.

-

Photograph by Daniele Raffo, 2005. LCREDIT: icensed under the GNU Free Documentation License, courtesy www.wikipedia.com.

Photograph by Daniele Raffo, 2005. LCREDIT: icensed under the GNU Free Documentation License, courtesy www.wikipedia.com.In the 1980s, France's President François Mitterrand inaugurated the Grands Projets, a multibillion dollar program of national-icon building. However, with the exception of I.M. Pei's glass pyramid at the Louvre, and Jean Nouvel's L'Institut du Monde Arabe, the buildings have been architectural duds: an overblown national library, a pompous office building at La Défense, and an unconvincing park of architectural follies at La Villette. Perhaps the grandest failure was the new opera house at the Place de la Bastille, which opened in 1989. The young Canadian architect Carlos Ott, chosen through an international competition, produced a cold and clumsy composition on the cramped site. Le Monde described it as a "rhinoceros in a bathtub." The only happy outcome was that Charles Garnier's wonderful 19th-century opera house, which the new building was to have replaced, has gained a new lease on life.

-

Photograph by Paul Warchol. Image courtesy Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, Architects, LLP, and Paul Warchol Photography.

Photograph by Paul Warchol. Image courtesy Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, Architects, LLP, and Paul Warchol Photography.Pei succeeded in Paris but stumbled in Hong Kong. The headquarters of the Bank of China was the tallest building outside the United States when it was finished in 1990. While the triangulated 72-story skyscraper was dramatic, it had the misfortune of being built only a few blocks from—and only four years after—a masterpiece: the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters. Foster Associates' 47-story building (the silver building in the center of the image at right) is considerably lower than Pei's, but it represents a radical rethinking of the high-rise office building, while the less-adventurous Bank of Hong Kong is merely an accomplished exercise in geometry.

-

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images.

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images.Like the Bank of China, the Getty Center was overshadowed by another building that was completed almost at the same time: the Bilbao Guggenheim. While Frank Gehry's museum was the quintessential iconic building of the 1990s—was it a fish, an artichoke, or a sculpture?—Richard Meier's campus of pristine glass and travertine was, well, just a campus. Not that a campus space cannot be iconic (think of Jefferson's central green at the University of Virginia, or Harvard's leafy quads), but that approach would have meant focusing on the landscape. Instead, Meier chose to tinker with the architecture, producing a collection of exquisite details that doesn't quite add up: a minuet, when what was called for was a symphony.

-

Photo by Dan Levine/Agence France-Presse.

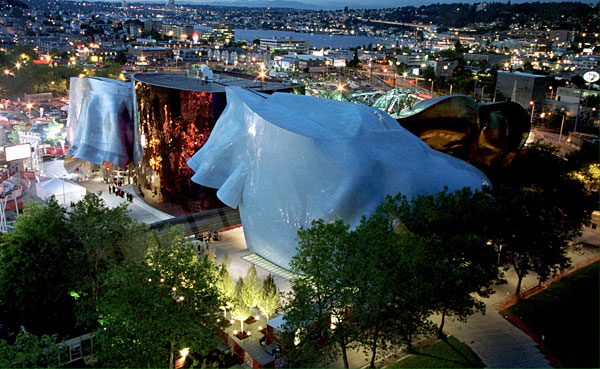

Photo by Dan Levine/Agence France-Presse.Clients sometimes commission architects hoping for an instant icon. That was certainly the case when, hot on the heels of the Bilbao Guggenheim, Frank Gehry was hired by the Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen to design the Experience Music Project in Seattle. But there is no such thing as an architectural Midas touch. The EMP is confused and confusing, a mishmash of forms, materials, and colors that tries too hard to be a literal representation of rock 'n' roll and falls flat. The architectural concept feels as forced as the whole idea of a museum dedicated to the history of popular music.

-

Photo by Index Stock Imagery.

Photo by Index Stock Imagery.London's ill-starred £789 million Millennium Dome, a celebration of technology and progress, was likewise meant to be iconic. Its failure was due in part to accompanying political scandals and in part to its lackluster contents, which failed to attract anything like the expected number of visitors. But the architects, the Richard Rogers Partnership, should not get off scot-free. Rogers, who is responsible for two architectural icons, the Pompidou Center in Paris and the Lloyd's Building in London, must have seemed the perfect choice. But while the structure is impressive as engineering, its iconic quality is minimal. It looks exactly like what it is: a tent. The real British millennial icon turned out to be the London Eye, a giant Ferris wheel beside the Thames.

-

Photo by William Thomas Cain/photodx.com.

Photo by William Thomas Cain/photodx.com.The original architect for Philadelphia's new concert hall was Robert Venturi, of Venturi Scott Brown. When he failed to produce a design that was considered sufficiently iconic, Rafael Viñoly was given the job. The acoustics of the resulting Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts received guardedly favorable reviews, but the architecture fizzled, especially when compared to that stunning icon, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which opened shortly after. What happened? The problem with the Kimmel is that it is a one-liner, and its one line—a vaulted glass roof—is just not that interesting. What do you do when your starchitect doesn't deliver the goods? Last year, the center took the unusual step of suing Rafael Viñoly Architects, ostensibly for cost overruns and construction delays, but according to the Philadelphia Inquirer "the underlying complaint seems to be that Viñoly failed to deliver a show-stopper." The suit was settled out of court.